Post (4) of a four-post essay. Post (1) is here, post (2) is here and post (3) is here.

The full essay makes up Part 4 of a broader series about language. It stands alone if that’s what you want out of your reading life, but for best results read the previous installments in the series — this, this and this — first.

In 1962 the German philosopher Jürgen Habermas wrote The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere. This was the first major book to talk about the public sphere, which Habermas defined as ‘made up of private people gathered together as a public and articulating the needs of society with the state’. In other words, it’s the domain where private citizens do politics, together.

The ideal public sphere is a peaceful forum where citizens discuss, debate and practise politics honestly, non-coercively and rationally. What does Habermas mean by “rationally”? Drawing on both Wittgenstein and the American pragmatists, he argues that reason is universal but not infallible: it’s less of a quasi-divine faculty and more a function of language.

When we talk to each other we naturally seek to co-operate and reach agreements, and the best way to do that is to come up with a set of procedures and rules for how to back up our claims so we can evaluate who has the best arguments. Reason is basically the overarching term for these procedures and rules — Habermas uses the term communicative rationality. This “procedural”, instrumental, pragmatic view of reason is more focused on living together harmoniously than being 100% LOGICALLY RIGHT.

In philosopher-speak, that means rationality isn’t objective, it’s intersubjective. Think of it like the hub of a wheel. Our various worldviews, religions, personal beliefs and lifestyles are like spokes: the wheel uses all of them, but they’re fundamentally separate to each other. The only place they all meet is in the hub. We’re never going to convince each other of our worldviews or 100% understand each other’s lived experiences. And reason isn’t a rich enough language game to express how our lives feel from the inside. But it is the only place all the spokes can meet.

Another analogy: think of rational argumentation like that smattering of English that enables you to get by in any one of dozens of countries all over the world. Could you have a more in-depth conversation with that Londoner if you learned their language inside out, or if they bothered to learn yours? Could you express more of your hopes, dreams and fantasies, more of what makes you you? Of course. But you’re only in London a couple of days, you’re just asking directions and the English you have is enough. It’s fit for purpose. Functional.

That’s what reason is for Habermas: functional. How strict your reasoning needs to be — whether you can get by with common sense or need to go full-on FACTS and LOGIC on your audience — depends on what you’re arguing for. Different discussions require different standards.

Couple of examples (mine, not his). If you’re petitioning for an access ramp for your local library, it’s probably not necessary to prepare a two-hour PowerPoint presentation about the moral implications of disability and the physics of wheelchairs. A simple ‘These people need an access ramp’ will do. But if you’re proposing something as technical and complex as, say, UBI, then your arguments need to be careful. And you need a lot of them. Has this been tried before, and what were the results? Do the numbers add up? How will different demographics, professions and regions be affected? Cost-benefit analysis please!

The strictest proofs of all are reserved for general truth claims (‘This isn’t my opinion, it’s just how the world is’) or issues of morality. Like a lot of philosophers Habermas distinguishes morality in the sense of “the ground rules we all follow” from ethics, meaning “taboos and aspirations that are personal to you and your group”. Morality is respecting human rights, ethics is going on a self-betterment course. Morality is ‘Thou shalt not kill’, ethics is ‘Thou shalt only eat kosher food’. Morality is a thin language, ethics is a thick one.

Habermas doesn’t say we should leave the thick language of religion, culture and ethics at the door when we enter the public sphere. He knows how much someone’s identity shapes their motivations, worldview and opinions. Instead, he’s making the subtler point that the more of reality your argument claims to describe and the more people who are affected by it, the more you should frame it in terms that everyone can agree on.

An argument like ‘God told me Lithuanian people don’t have rights’ would fail Habermas’ test because (a) you can’t reasonably convince people that God told you anything — a lot of the citizens you’re talking to don’t even believe He exists — and (b) your conclusion moves beyond your personal ethical system and messes with the morality we all live by in a democracy. Not only would implementing your suggestion directly harm a specific group of people, it would weaken society itself by destroying its founding principles — human rights and equality. Hacking at the foundations of society harms everyone.

Similarly, if you decide to treat people less fortunate than yourself compassionately in your private life, that’s a matter of personal conscience. But if you argue in a public forum that a particular group should be assigned a specific legal status that goes above and beyond the standard rights that apply to us all, then you’re making a moral argument in Habermas’ sense. Why? Because even though not everyone belongs to the group in question, implementing your proposal would involve changing the law of the land, which does belong to everyone. That means your arguments need to be solid.

Which isn’t to say that everyone in the country needs to agree with your proposal before it’s OK to sign it into law — haters gonna hate. It isn’t even to say that all prospective laws need to be debated widely.

It just means that public arguments for public proposals need to meet certain standards. Yes, people are complex, and you can’t prove a social theory with the same rigour that you can prove that 2+2=4. But that doesn’t mean you can make do with assertion alone. Your arguments have to be comprehensible to all of your listeners in principle — in the “thin” sense of understanding someone who’s asking for directions, even if not in the “thick” sense of understanding your perspective from the inside out. They need to appeal to common principles rather than authority, rely on your knowledge rather than your status, persuade rather than coerce. They need to be reasonable.

We only have universal rights, secularism and liberal democracy because the Enlightenment philosophers saw that appeals to authority — the authority of personal experience included — always set one group off against another. After all, no “thick” language saturates every aspect of your identity and lived experience as much as the language of religion, and it’s exactly this fact that caused religious people to massacre each other for centuries. While religious violence still exists, widespread secularism has massively lessened its impact by robbing it of legitimacy.

That’s why the Enlightenment revolutionaries set their new nation-states up on principles that ignored all people’s most deeply held convictions, their most deeply lived experiences. The alternative was to go on having war after war and massacre after massacre: the Crusades, the pogroms, the unending battles between Catholics and Protestants, and on and on and on.

SO WHAT DOES ALL THIS LOOK LIKE IN PRACTICE?

This essay has been pretty abstract so far. So here are a few concrete examples of the principle that political arguments need to be broadly understandable and meet a minimum criteria of reasonableness.

First off, immigration. We’ve become used to the stereotype of conservatives being the fact-lovers and liberals being the feelings-havers, but that’s a very recent distinction. Actually, if you believe Jonathan Haidt, the conservative worldview is far “thicker” and more emotionally layered than the liberal one — in Haidt’s terminology, conservatives have more “moral tastebuds”.

This doesn’t mean that conservatives are better people — it’s more like they shock easier. Where an old-school liberal is more likely to advocate a “thin”, narrowly rational morality like ‘Do what you want as long as you don’t hurt others’, an old-school conservative is more likely to talk in the vaguer language of emotion: they’re proud of their national heritage; their own religious beliefs feel right and things like gay marriage, prostitution, free love and Islam feel wrong. Their political worldview is composed of more linguistic layers, more shades of emotion.

Over and over again through the last 500 years conservatives have desperately tried to cling on to the cultural institutions they felt were slipping away, while liberals hacked one after another of them to ribbons with the SHALOL, crying ‘Facts don’t care about your feelings!’ Over and over, conservatives have plumped for a “thick” conception of tradition and heritage, while liberals have pointed out that all cultures are relative, all traditions are only so many years old and it’s secular society’s job to tolerate every lifestyle as long as people sign up to the bare minimum of democracy and human rights.

Hence the eternal debate around immigration. One of the strongest emotions powering old-school conservatism has always been a wariness around people from different groups, especially people from very culturally different nations. Liberals, lacking this wariness, have always said that if you keep to the facts it’s obvious that immigration is a net social benefit. The challenge they face in 2020 is resisting the temptation to let the extreme end of modern conservatism (‘Close the borders!’) goad them into an equally emotive response. When the facts speak for themselves, considered arguments always stand a good chance of winning the day.

Next up, diversity quotas. I don’t have a firm opinion on what are and aren’t appropriate ways to ensure fair representation in the workplace. But I do know that economics is a complicated beast, equally bound up with the “soft” world of psychology and sociology and the “hard” one of numbers, stats, FACTS and LOGIC. So it’s not enough to say ‘Every example where a specific group is underrepresented is an example of prejudice’ and call it a day.

The quota discussion is a great example of a debate where your arguments have to be understandable to everyone — in principle — because the issue affects everyone. Changing the way companies hire their employees impacts not just marginalised groups, but all of society (whether directly or indirectly). There’s also the question of whether quotas hurt the very groups they’re trying to help. Maybe they do, maybe they don’t, but you can’t figure it out without the numbers.

That’s why measured analysis like this is the way to go here. The document’s written from the perspective of people who want to help women achieve their full potential, but it starts out by admitting that the quota issue is a complex one and that there are costs and benefits to everything. Reasonable, nuanced arguments about complex economic phenomena: this is how the public sphere works when it’s working right.

I decided diversity quotas weren’t controversial enough, so I’m going to quickly bring up abortion. This debate is one of the ones most frequently associated with the “lived experience” perspective. Because women have to carry babies for nine months and are frequently forced to bear disproportionate responsibility for them when they’re born, they often (understandably) argue that men don’t have enough skin in the game to participate in the discussion. And many men agree.

But when you’re debating the moral status of something or discussing whether a specific group is entitled to human rights, that means you’re talking about not just an everyday ethical issue but the law of the land, and not just the law of the land but the most fundamental values and protections that underpin the very foundation of the law of the land. Debates like this fall under the definition of the “thin” matters of morality that concern every citizen in a participatory democracy, which means that all citizens are entitled to a say on the matter.

If a compelling case were made that foetuses don’t deserve fundamental rights and protections, then their impact on the female experience would probably be the most important thing about them. But if they do deserve the law’s protection, then this fundamental moral claim is the most important thing about them. Until this question is resolved — via reasonable, evidence-based arguments that everyone has a right to put forward and an ability to understand in principle — then it isn’t possible to say that lived experience is the only relevant factor in the debate.

It’s not that the experiential dimension should be ignored. But it also can’t be used to claim unassailable authority on moral issues, any more than religion can. It’s understandable why people find appeals to experiential authority more legitimate than appeals to religious authority — at least everyone can agree that your experiences are real — but when it comes to debates over legal status, human rights and objective morality, any privileging of authority over mutual agreement-reaching doesn’t entirely do the issues justice.

MOVING TOWARDS MUTUAL UNDERSTANDING

I think Habermas’ theory of the public sphere is a good way of reconciling lived experience with FACTS and LOGIC, instrumental reason with objective truth, everyday life with politics and the variety of humanity with the variety of ways you can argue in public.

People often use what seem like LOGICAL FACTS to reach what seem like distasteful conclusions. But I think that once you’ve set up humane ground rules for a political debate — human rights, fairness, equality and so on — then any logical argument that reaches a horrifying conclusion isn’t a sufficiently logical argument. We’re back to Carl the Friendly Logical Robot from my first post: his problem wasn’t that he used reason, it’s that he was fed the wrong data. A lot of the arguments that turn the “lived experience” camp off just aren’t very good arguments, and the best remedy for them is better arguments.

Of course, most public discourse doesn’t get anywhere near Habermas’ ideal. We’re not solving much with Twitter wars, smackdowns, clapbacks, DESTROYED students, bad faith arguments, gaslighting, whataboutism, ad hominems, empty signalling and blatant power moves. It’s hard to know how to even start addressing the problem, but I’d love to see more schools and universities teaching systematic critical thinking and rational disagreement as core subjects.

The public sphere we need to move towards is a halfway house between the “thin” and the “thick”, the moral and the ethical, the emotional, personal, anecdotal language of everyday life and the detached, generalised language of politics. Its debates are inevitably motivated by people’s perceptions, biases, lifestyle and personal beliefs, which is a good thing — these are the things that make life worth living and arguments worth having.

But town hall debates, newspaper articles and TV appearances raise the stakes of a discussion, which means the standards have to be raised to match. You’ve got to consider your proposals’ implications for everyone who could possibly be affected by them, and make your arguments work for people who don’t share your identity, experience, lifestyle or beliefs.

Naturally, this is tricky when the subject at issue is your identity, experience, lifestyle or beliefs. When you’re arguing that your group needs additional legal protections. That the pie isn’t divided fairly. That the system is stacked against you.

Like with everything else in life, it’s a matter of balance: your arguments may be fuelled by your passion and your personal stake in the matter at hand, but those things aren’t enough to provide a bridge between you and your listeners. Reason — whether in the strict sense of FACTS and LOGIC, with its stats and graphs, or the slightly less strict sense of reasonableness, with its common sense and common humanity — is that bridge. Without it, argumentation becomes nothing more than emotional manipulation or a series of power moves: claiming special status, social shaming, veiled threats. These aren’t healthy things to introduce into political discourse even when you’re in the right.

The good news is that in a healthy public sphere there’s no need for these tactics. If your cause is just, then the key facts are on your side. This may mean you can point to a series of clinical studies, sociological surveys and statistical graphs that back up your argument.

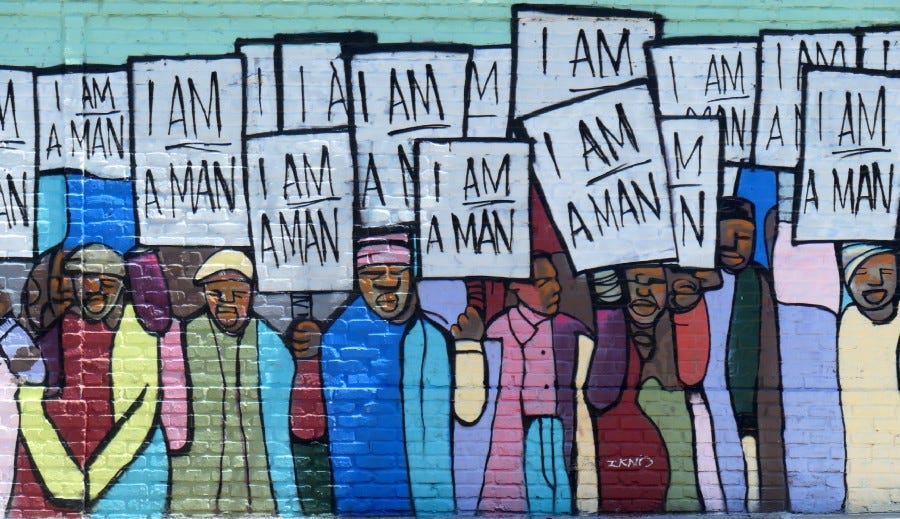

But often it’s just a matter of pointing out to your audience that your common humanity means you deserve the same consideration they do. That’s the kind of reasonableness the Shakespeare character Shylock appeals to in his famous speech: ‘Hath not a Jew eyes? Hath not a Jew hands, organs, dimensions, senses, affections, passions; fed with the same food, hurt with the same weapons, subject to the same diseases, healed by the same means, warmed and cooled by the same winter and summer as a Christian is? If you prick us, do we not bleed?’

It’s difficult to win people over by arguing that the texture of your life is something they can never understand. But you’ll win them over if you can show them that although you may seem very different to them, you’re fundamentally made of the same stuff. By respecting your difference, they affirm your sameness.

The world’s an unequal, cruel place, tainted by systemic injustices and abuses of power. Lived experience is where we confront the pain of this reality. And reason is how we convince people to create a new reality.