Further Up and Further In

Why do paradoxes express more truth than clear statements?

Although this post can be read alone, it’s also Part 2 of a philosophy series called “Everything’s True At Once”, which argues that (a) we don’t believe things for the reasons we think we do; (b) any one of us can only see a small part of the overall truth; (c) most of our apparent disagreements consist of one person seeing the yin, the other seeing the yang and neither seeing how they fit together; (d) competing worldviews are more like different music genres than truth claims that are truer or falser than each other; (e) balance within society and the individual can only be achieved through diversity of opinion; and (f) a statement’s impact is more important than its accuracy.

Part 1, which covers (a) and (b), is here. This post tackles (c).

YOU SAY POT-AY-TO, I SAY POT-AH-TO, LET’S CALL THE WHOLE THING YET ANOTHER UNRESOLVABLE PARADOX

Ram Dass has a line I love about how your worldview expands the more awake you become. He calls it a process of ‘Oh, this as well’. Basically, instead of rejecting belief system after belief system until you arrive at the Correct Set of Beliefs, it’s more like you see how all the things you’d previously been inclined to reject were part of the picture all along. (I can’t remember what talk this is from, so I might as well link to this one because I like it.)

In my own small way, I can identify with this. There’s nothing more satisfying than realising that two worldviews that have been duking it out in your head for years can actually be brought together in a Hegelian synthesis: oh, this and that. Suddenly dark and light, reason and intuition, yin and yang, aren’t fighting each other but complementing each other, not fully themselves without each other.

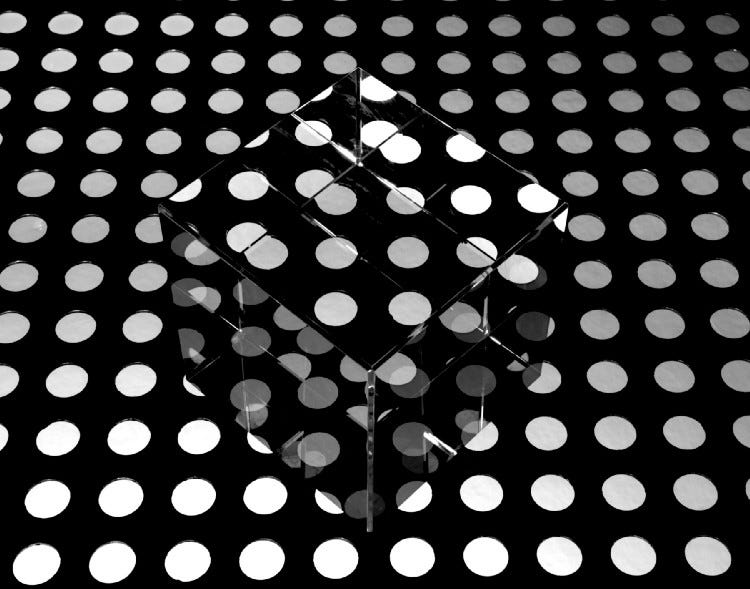

It’s like those famous images that can be interpreted as one thing or another, but never both at once. After spending half your life only being able to see the rabbit and the other half saying ‘Oh, it was a duck all along!’ you finally realise that the image was always both a rabbit and a duck. Maybe you even develop the ability to flip between the two images at will.

I see the rabbit/duck effect coming up in philosophy so much that at this stage it’s harder for me to think of things that aren’t paradoxes than things that are. Here are twenty-eight examples of what I mean.

Life is meaningless because meaning tells stories about reality instead of experiencing it directly; but direct experience is the most meaningful thing of all. Fate is both tragically serious and a massive cosmic joke. Our spiritual life is about expanding ourselves, but also about waking up to who we already are. This takes a huge effort and no effort at all. The kingdom of heaven’s both out of reach and within. We’re simultaneously better and worse than we think we are, selfish through and through and doing our best. Life’s about fully mastering ourselves and fully expressing ourselves. It’s about loving without reservation and protecting our boundaries so assiduously people don’t even think about taking us for granted.

We’re products of our environment and completely autonomous; we need each other and stand alone. We do and don’t have free will, everything and nothing is our responsibility, and we are and aren’t guilty of our sins. Spiritual growth involves acquiring insight after insight and dropping concept after concept. It takes obsessive singlemindedness and a perfect sense of balance. It adds both nothing and everything to life. Our thoughts shape reality and reality shapes our thoughts. There are no objects without a subject and no subject without objects. Belief informs action, but action creates belief.

The physical world is and isn’t an illusion. Suffering is and isn’t real. Reason is a supernatural power and an invention of the human brain. Our mind creates our body and our body creates our mind. We’re all individuals and all the same entity. God is and isn’t a person. He’s in every cell of our being and totally beyond us. We don’t even exist in any meaningful sense of the word, but we absolutely exist in the only sense that matters. Everything is composed of limitless emptiness and indescribable fullness.

All of this might come across like wordplay for its own sake, or a flippant attempt to emulate the cryptic mysticism of the Tao Te Ching. But I genuinely believe each of these statements, and think all of them can be defended on their own terms. In fact, they all interest me so much that in an ideal world I’d write a separate essay about each one (in the real world, where writing about metaphysical stuff takes time, I’m hoping to get to a few — eventually).

For now I’ll just ask: if you can counter any provocative generalisation about life with another generalisation making the complete opposite case, what’s the point of making these statements at all? You could say there’s no point, but surely it’s kind of important whether we’re responsible for our actions or not, whether the physical world’s an illusion or not and whether humans are fundamentally good or not? So what’s going on here?

MOTORBIKES, KNIVES AND THOSE WEIRD QUANTUM THINGS

The main problem is with language itself. It likes pinning things down, which is a perfectly noble ambition, but sometimes it gets a little carried away.

This is especially true in our logic-drunk era, which can’t hear ‘This thing is this way’ without auto-completing with ‘Which means it isn’t that other way’. 2 and 2 are 4, which means they’re not 5. I’m young, so I can’t also be old. Of course, this methodical precision is highly useful. In the 1970s classic Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, Robert M. Pirsig compares reason — and conscious awareness itself — to a knife that cuts the world into manageable pieces. Rasmus Grønfeldt Winther agrees: ‘We are always slicing single reality conceptually in order to understand it, interact with it productively, and find ways to change it.’ Essentially, if you imagine the reality we experience as a giant pie, then reason is what divides it up into slices and compares them with each other: ‘This one’s a little bigger, this one has more crust…’

The benefits of dividing up the pie are enormous. Suddenly the world isn’t overwhelming and chaotic. Like Adam naming the animals, we can distinguish phenomena from each other, figure out how they work, manipulate them and use them for our benefit. Enter mastery. Science. Medicine. Technology. It’s a process we learn over time: newborns can’t distinguish I from Thou and This from That at all; children are better at making distinctions; adults better still; some adults can do it better than others; we call those people mathematicians and logicians.

The mistake we make is in thinking that the analytical mind of the adult is more right about reality than the “oceanic consciousness” of the infant, rather than just more useful for physical survival. Categorising, labelling and defining things helps us determine which foods are edible, invent timesaving devices and plan for the future — basically, ensure our comfort and longevity — but it doesn’t necessarily honour the full extent of our nature and it certainly doesn’t constitute the only way of apprehending reality.

That’s why so many mystics seek to “get back” to the Great Ocean of infancy and integrate it with the rational consciousness of adulthood. They’re tired of the logical mind’s insistence on only feeling one part of the elephant at a time. They want it all.

For Pirsig, rationality is a deceptive tool that hides as much as it reveals. He compares its categorising and dissecting of reality to the process of labelling the various parts and functions of a motorbike: ‘there is a knife moving here. A very deadly one; an intellectual scalpel so swift and so sharp you sometimes don’t see it moving. You get the illusion that all those parts [of the bike] are just there and are being named as they exist. But they can be named quite differently and organized quite differently depending on how the knife moves’ (emphasis mine).

In other words, when you classify things and compare them to one another you’ve always got to keep in mind that you’re the one doing the categorising. You could divide everything up completely differently — cut the pie into a different set of slices — and they’d still add up to the same pie. The implication is that what we call “facts’’ are often just arbitrary name tags that we conveniently slap onto experience — all-too-human ways of coping with the infinity of what’s around us. If enough people agree with your labelling system, you can call it “objective data”.

But some things just are facts and some things just aren’t, right? What about scientific truths like ‘The Earth goes around the Sun’? You can’t sneak a Zen paradox in here and say ‘But in a way, does the Sun not also go around the Earth?’ No. The Earth goes around the Sun, we’ve tested it, we can demonstrate it, end of story. You have to draw the line somewhere, right?

I’m not so sure. The problem here is that we’re just calling the Sun the Sun and the Earth the Earth for convenience. One is a catch-all term for a big thing we’re all standing on different sections of, and the other is a catch-all term for a bigger thing that gives us the light and heat we need to stay alive. But you could also choose to ditch the catch-all terms, declare that “Sun” and “Earth” are just human name tags, and say it’s all just molecules whizzing around when it comes down to it: some clump together, others don’t, why label any of them. Then you could say that “molecule” is just an arbitrary name tag and it’s all just subatomic particles dancing around — but “particles” isn’t the only useful way to describe subatomic phenomena — in fact ordinary language can’t seem to capture what’s going on down there at all — so the deeper we look the less we see, and the more we try to clarify things the muddier they become. That doesn’t mean scientific labels aren’t useful. But it may mean they’re not the One And Only Truth About What We See.

Even the statement ‘Just trust the evidence of your eyes’ is problematic, as Kant pointed out. Your eyes aren’t telling you anything unless you interpret the information, and your interpretations need to hang together logically, but logic is a human thing not an out-in-the-world thing, so how can we trust what it’s telling us about the world? But we don’t want to get stuck there, so we compromise and say yes there’s an objective world out there and yes there are our subjective interpretations of it, and the two interact in complex and ever-shifting ways. But as soon as you try and define exactly what those “ways” are, you run into problems again.

KNOWLEDGE, WISDOM AND COMPETITIVE SHADOWS

For me, grasping the essential flimsiness of the logical truth we call “knowledge” makes it easier for me to accept the anti-logic of the paradoxical truth we call “wisdom”. In the world of rational knowledge, two contradictory things can’t be true at once: if this is the bigger slice of the pie, it can’t also be the smaller slice. But from the “wisdom” perspective, it’s all one pie. If two things seem to be in contradiction, it’s because the mind has created the contradiction then tried to “solve” it. By seeing that the contradiction needn’t be there in the first place, you don’t “solve” it but rise above it altogether.

Reason slices the pie in two then declares that the two pieces aren’t the same. Wisdom says they were the same before they got sliced up. And, essentially, they still are.

When the mystics say ‘It’s all one, man’ I think this is a large part of what they mean. All divisions and categories are man-made, so try dropping the labels and experiencing the whole pie at once. This is a more expansive, generous and relaxing way of perceiving, and on the very few occasions I’ve been permitted a tiny glimpse of the Whole Pie I’ve realised just why people spend their whole lives trying to see this way permanently. In fact, I don’t think talking about pies and slices quite captures how rich the “wisdom” perspective is. Maybe dimensions would make a better metaphor.

Imagine living in a two-dimensional world, a Flatland that only contains length and width. For me, the easiest way to wrap my head around this is to picture myself as a shadow: because they have no mass, it’s impossible to stack them on top of each other. If someone casts a shadow on a particular spot and fifty other people come along and cast their shadows on the same spot, the dark patch doesn’t rise any higher than it was before. It’s the same perfectly flat absence of light as ever. Shadows are consistent that way.

So say you’re a shadow, walking along doing shadow things. Now say you come across another shadow and say ‘Hey look, I’m ahead of you, you haven’t caught up to me!’ They reply, ‘No, I’m ahead of you and you haven’t caught up to me!’ From your Flatland perspective only one of you can be right: either you’re ahead of your friend, or they’re ahead of you. You can’t both be ahead because that would be a logical contradiction — stands to reason. There can only be one winner here.

Now picture yourself as a human being looking down at the two shadows arguing. From your perspective their war of words is completely uninteresting: they’re both below you, and that’s all that matters. There is no “ahead” or “behind” from this vantage point, only “above” and “below”. But now say you and another person are catapulted into space together: it’s “above” and “below’s” turn to get transcended. And if you were a fourth-dimensional Time Lord you wouldn’t have much use for terms like “before” and “after”. And on it goes.

Eventually all vantage points melt away, and in Ram Dass’ words, you have “nowhere to stand”.

The crucial point here is that while you watch the shadows arguing you’re not contradicting either of them — they’re contradicting each other. Instead, you’re refusing to engage with the debate at all because the words it’s framed in are inadequate. You’ve transcended that level of argument altogether. Volume doesn’t “contradict” length or width; it adds to them, expands their possibilities, puts everything they’re capable of within a larger framework. So both of you shadows are ahead, neither of you are ahead, forget ahead, just look up.

OR SHOULD I SAY FURTHER UP AND FURTHER IN

To me, the dimensions analogy explains the everything’s-a-paradox/rabbit ‘n’ duck/‘Oh, this as well’ phenomenon. Rather than any particular point of view being the One True Way to Look at Things, you have layer after layer of different perspectives overlapping with each other, stacking on top of each other, reacting to each other. This makes even the most narrow-minded perspectives not necessarily “wrong” so much as limited: they nest inside more expansive, holistic perspectives like Russian dolls. The more we learn and grow, the more we become like bigger Russian dolls containing lots of smaller ones.

The beauty of the “overlapping perspectives” way of looking at things is that it’s endlessly flexible. You can even turn it back on itself. So it’s not just true that everyone’s point of view coexists in harmony: some things are straightforwardly untrue; some things are straightforwardly better than other things; it’s kind of true that we can’t know anything at all; it’s kind of true that we’re surrounded by objective facts and they’re ours for the taking; it’s kind of true that facts are what we make them; it’s kind of true that everyone sees reality in a different way; and it’s kind of true that we’re all saying the same thing because We’re All One and Truth is One.

Yes to all these perspectives, and yes to every point of view in between. Different circumstances call for different emphases, that’s all: if a scientist keeps going on about Cosmic Oneness she’ll be kicked out of the lab, and if you keep insisting to your friends that We Can’t Know Anything Really So Why Bother Discussing Things they’ll stop calling you. Context is everything.

Robert M. Pirsig and Ram Dass are scholars and gentlemen, but I’ve got to give the last word on all this to C. S. Lewis, because I like him and he deserves it. There’s a beautiful passage in The Last Battle, my favourite in the Narnia series, that comes after the main characters enter a stable that turns out to be a portal to the afterworld. After looking around a bit they realise they haven’t left Narnia at all, they’re just in a bigger, better version of Narnia — ‘a deeper country’ where ‘every rock and flower and blade of grass looked as if it meant more’. Best of all, this epiphany is only the beginning: Aslan instructs them to keep exploring, higher and deeper, on and on, ‘further up and further in’.

The gang don’t need to be told twice and keep penetrating deeper into the New Narnia until they reach a garden-that’s-not-a-garden. After studying her surroundings carefully, Lucy has this exchange with Mr. Tumnus the faun:

‘I see,’ she said at last, thoughtfully. ‘I see now. This garden is like the stable. It is far bigger inside than it was outside.’

‘Of course, Daughter of Eve,’ said the Faun. ‘The further up and the further in you go, the bigger everything gets. The inside is larger than the outside.’

Lucy looked hard at the garden and saw that it was not really a garden but a whole world, with its own rivers and woods and sea and mountains. But they were not strange: she knew them all.

‘I see,’ she said. ‘This is still Narnia, and more real and more beautiful then the Narnia down below, just as it was more real and more beautiful than the Narnia outside the stable door! I see…world within world, Narnia within Narnia…’

‘Yes,’ said Mr. Tumnus, ‘like an onion: except that as you go in and in, each circle is larger than the last.’