Eta sits for a moment thinking about what to tell the assembled company and what to leave out. They’ve been rehearsing for this moment for days, but it’s one thing to imagine Chi’s imperious stare boring into your brain, and another to experience it in person.

The others don’t have it in them to understand, they tell themselves for the hundredth time. They’re all such short-term thinkers, doubly so now that they’re up against the wall. They’d never be able to see that less to go round now means more for everyone later. And the Temels are so close. A couple more years of tinkering should do it. By the next council I’ll have my fait accompli and the rest will have no choice but to admit my strategy worked.

‘Just reminding you that this portion of the meeting was your idea,’ says the reliably impatient Rho, drumming their fingers on their axehead.

Eta looks around at the waiting faces and steels themselves. This won’t be easy.

‘Our predicament in the Deep Bracken can be summarised in two words: resource depletion,’ they begin. ‘Even in an area as tree-rich as ours, there are only so many specimens whose wood is suitable for the kind of construction we do. And there are only so many mushrooms and herbs fit to export. As for our crops, we’re not doing much better than the Polems — one bad harvest after another. Of course you’ll have noticed we’re bringing a little less to the market each year — ’

‘Hard not to notice,’ says Chi.

Eta continues, ‘The Innovations have come to a standstill. The more we’re forced to attend to matters of basic survival, the less time and resources we have to devote to our critical new projects. What’s so frustrating is that the whole purpose of our work is to lift us out of our poverty in the long run. If we can figure out ever-newer and better ways to extract food from the ground and bark from the tree, the hope is that we will eventually claw our way out of this perpetual cycle of plenty and scarcity — what Tau calls the “natural rhythm” — and unleash an era of reliable abundance. But for now, things are so scarce that we have to put this vital effort on hold — prevented from finding the solution to our problem by the very scale of the problem!’

‘Top-tier lyricism, Eta — you could have been a bard in the old days,’ comes the adamantine voice from the south-facing throne. Eta flinches. Yes, Rho’s reactions are proving significantly more intimidating in person than they appeared in the Temel’s imagination beforehand.

Rho’s eyes seem to turn in on themselves and stare harder into Eta’s all at once, a neat trick. ‘Unfortunately for you, though, merchants talk to each other, and I don’t get all my news from these little bulletins of yours. I have it on what I consider good authority that your harvests have never been fuller, your timber yards are overflowing and your granaries are bursting. Far from starving for resources, you’ve been stockpiling them. Why I don’t know. Maybe you’d like to enlighten us?’

Chi traces shapes along the long arms of their north-facing throne and stares up at the moons through the skylight. ‘Yes, maybe you’d better, Eta.’

Eta does their best to match the intensity of Rho’s stare, eyeball for eyeball. ‘And what do you consider to be “good authority”, friend? Better than, oh, the word of a druid of equal rank you’ve worked alongside for a dozen hundred years?’

The Polem sneer-smiles — another neat trick. ‘The best of all: my own eyes. Or as near as makes no difference. I was becoming increasingly troubled by some of the reports filtering through from my traders, so last small-moon-cycle I sent a few scouts down to the Deep Bracken to see what they could see. Of course, they couldn’t get past the outskirts of your habitation — your crowd has seen to it that you’re well walled off from public view. But they saw enough. They reported that they had never seen so many breaks in the treeline. That your oak-felling had reached such a pitch that large swathes of your land were starting to resemble the Clearing.’

Chi murmurs something under their breath, while Tau looks positively wounded. The idea that anyone would take anything from their surroundings beyond what’s strictly necessary to keep the wheels of trade in motion is anathema to the modest Kalli. Eta suppresses a growl. The problem with the mystical view isn’t that it’s imprecise or impractical — it’s that it’s so conservative.

Eta thinks hard. The substance of Rho’s accusation is plain: the Temel has committed the cardinal sin, that of being a Hoarder, a Bad Coordinator. The druid is well aware that in theory, resources belong to the Four Tribes in common and are distributed where they are most needed. The idea that one community would accumulate wealth at the expense of the others runs counter to everything that the present epoch is supposed to stand for. In a perfect world we’d trust each other enough to let the best and brightest amongst us think a little bit ahead, Eta says to themselves. But this is not a perfect world.

The chameleonic Temel struggles to retain their composure. ‘If you think so little of me, my Polem friend, I wonder how you’ve kept your counsel this long. Where were these accusations earlier in the evening? Manif’s, I’m surprised you didn’t blurt them out during the rites.’

Rho’s smile somehow manages to thin further. ‘Maybe all these lean years have taught me a bit of that patience you’ve always said I lacked, Eta. Honestly, I wanted to wait and see what you came out with. When I’m told a fellow druid is keeping something from me, that gives me valuable information about the diplomatic company I keep. But when that same druid lies to my face — in the sanctity of the throne room — that gives me more information again. It’s important I know exactly who I’m dealing with, no? Well, I have a pretty good idea now, don’t I?’

Eta, by now fighting down waves of anxiety, quickly scans the room. Of course Tau is staring at the floor again. Chi looks haughtily disapproving, no surprise there, but also strangely…amused? The imperious Sofali has been acting strangely all evening, Eta decides. Even smugger than usual.

The druid’s mind whirs a million tree-lengths a minute. They’d been afraid of this: hack down every tree in sight and you’ve made yourself conspicuous, even in the atmosphere of benign Balkanisation that characterises this time and place. But there’s still no question of telling the whole truth. Recounting the unfiltered story of the Temels’ extraordinary last few years would obliterate the fragile equilibrium of the council, and in this cursed age, the council is the only thing preserving the equilibrium of the entire Great Forest.

Eta has been lying, yes, but only in a sense. The Temels are suffering from acute resource shortages, just not of the nature the druid has been describing.

The truth is that the tribe is progressing at such a pace that they’re running out of raw materials to stoke the furnace of their ambition. Every fresh Innovation transforms agriculture so profoundly the tribespeople have more food than they know how to eat, and generates revenue so quickly it’s paid for itself within days of its invention. A new economy has arisen based not on consistency but on growth, destabilised by one Innovation only to be restabilised by the next one, scared not of starvation but of stagnation. Having now fed and housed the tribe, all the labour-saving apparatuses and contrivances have coalesced into a mechanical monster itself in constant need of feeding. If this Moloch is to have enough to eat, the Temels will eventually need to hack down every tree from here to the edge of the Great Forest.

The truth behind the truth is that the Innovative method has taken on a life of its own; that each new developmental pathway is branching off into another dozen pathways; that the secrets of the universe are laying themselves bare before the Innovators’ astonished eyes; that those secrets have little to do with magic or oracles. The current evidence suggests that reality is lawful, and that every advance in knowledge entails a corresponding increase in power. It’s but a short step from understanding what comprises objects and the forces that power them to constructing one’s own objects and powering them with one’s own forces.

The Innovations’ dangerous potency has already triggered a slew of unpredictable changes in Temel society. Remove all external pressures from a populace and they’ll busily generate internal conflicts as fast as they can think of them. Peasants liberated from lives of basic subsistence almost overnight have found they don’t know what to do with their newfound freedom and are looking for trouble. All over the Deep Bracken long-buried intratribal grudges are being resurrected by the day, and there have even been brawls in the streets, some lethal. The phrase “civil war” is unknown in the Great Forest, but the way things are going someone will have to coin it soon.

All of which would be concerning enough without the Temels’ recent fertility boom. At the current rate all those surpluses are going to turn into shortages within a couple of years, Eta has thought a thousand times, and what will that mean for tribal harmony? Resentments and feuds that appear pressing now will seem like matters of life and death once there are actual stakes involved, and the druid has spent many sleepless nights imagining the various factions fighting over resources, tools lying unused in their workshops, perfectly good brains being splattered over the forest floor before they have the chance to solve the great mysteries of the age…

As Eta sees it, there’s only one way for the Temels’ brave new society to keep from imploding before it’s even found its feet: spread out. Yet another unsayable idea in this static, rule-bound era, but it’s the only way to secure more raw materials. More farmland. More room to live. Perhaps most importantly of all, it means adventure. Expeditions will be the vessel into which this most boisterous of tribes can channel all their newfound energy. In a world without intertribal conflict, exploration is the only common cause that will suffice to bind the restless Temels together again.

And what might be out there? Eta has often wondered. In their heart of hearts, the druid’s ultimate ambition is to ascertain if anything lies beyond the Forest’s leafy borders — this in direct violation of the cardinal rule laid down by the Manifestations all those aeons ago. The great oaks that once symbolised shelter and protection have started to feel like prison bars. Eta longs to rip them all down and breathe the open air.

The slender Temel sits struggling to decide how much of all this to divulge to the rest of the council, and how best to frame it. If you’re telling the truth details add clarity, but if you’re only telling part of it they just add complexity. But it’s evident from the way Rho is fondling their axe that Eta needs to give the others something, and fast.

If you want to get out of this, it’s going to have to hurt, they think to themselves. They know you’ve been hiding things. The only way to halfway placate them is give them some of what you’ve been hiding, something you’d much rather keep hidden. When you’re being chased by ravenous dogs you have to throw them a little meat before they get their teeth into you.

They reach a decision, and fix their gaze on their Polem accuser. ‘Fine, Rho, you win. Yes, we’re chopping down trees at double the sustainable rate. Yes, we’ve been withholding goods from the market. But that’s not because we’re hoarding. It’s for the simple reason that there are…’ — lowering their gaze, this is difficult — ‘…more of us than there used to be. More citizens means more provisions, more dwellings, more farm equipment, more bark-tools.’ The wood of the Great Forest is to its earthly counterpart what steel is to clay.

Eta masks their unease with a small dose of sarcasm. ‘Our latest arrivals will insist on feeding themselves, housing themselves and contributing in some way to the common good. All of which requires raw materials, and plenty of them. That’s just the way it is.’

The others look predictably uncomfortable. Tau frowns. ‘You haven’t chosen the most opportune moment for a population spurt.’

‘We didn’t exactly choose it, did we?’ Eta bites back.

Sex and romance are unknown to the Forest-dwellers, of course, with all arrangements of association and cohabitation based purely on compatibility and convenience. House-sharing agreements are neither official nor binding, and can be altered at a moment’s notice. There is no limit to the number of adults who can share any given space, or the spaces a particular adult can be said to reside in, and child-rearing is a loose, communal affair.

Reproduction, meanwhile, is an asexual, sudden and purely random matter; Forest-dwellers can no more decide when or how many times they will give birth than you or I can pause our heartbeat. This makes infanticide the only realistic form of population control, and that particular practice has been frowned upon since the close of the Days of War. Still, Eta has grown to suspect that fertility has less mystical origins than is commonly believed; the correlation between the tribe’s latter-day access to reliable nourishment and their sudden “productivity” could well speak to some deeper causation.

‘Things will level off in the end,’ Eta goes on. ‘They always do. The wave rises and the wave falls, as one of your old songs goes, Tau. But in the meantime, we have to do what we can to provide for those we’ve got. In the short term, that means overforesting. But when things go fallow again the trees will grow back, as they did the last time and the time before that.’

Exhaling with an effort, the druid scans the room once again. The others look more uncomfortable than ever, and none seem satisfied. Fertility is a deeply taboo subject in the Forest, and is generally not discussed unless absolutely necessary — not even in the most abstract, statistical manner, not even when it’s directly relevant to the point at issue, not even in the halls of power. Eta has chosen their almost-but-not-quite-unsayable diversion well.

Finally Tau breaks the silence. ‘You could have said all this at the outset. I appreciate how difficult it is to broach the topic, but we’re all druids here, and it’s not as if the rest of us would have held your population difficulties against you. We’re in a time of unprecedented crisis, after all, and we need to lay everything on the table. Better we risk finding each other, um, gauche than end up suspecting one another of being liars and hoarders.’

Strong words for the meek Kalli, and Eta fights to stop their nervousness mutating into genuine panic. ‘Forgive me, Tau, for being less than completely open with the council,’ they say, their voice as steady as they can make it. ‘But I hope you can see that the substance of what I said was sound: my tribe is stretched to breaking point, we can barely feed ourselves, we have nothing to spare. If I dissembled a bit on why that’s the case, it’s because it’s a sensitive subject, it’s not strictly relevant to the matter at hand, it’s not really the rest of your concern, and I thought we all trusted each other enough to know none of us would ever withhold from the market without good reason.’

They convert as much of their anxiety as they can manage into defiance. ‘By the way, I thought this was a council, not a trial.’

Rho stares up at the moons, and affects a distant, whimsical tone. ‘Oh, I almost forgot. A couple of your traders also mentioned something about a…well. They hinted that it was set to host events that would soon shake the whole Forest, but declined to say why. And now here the four of us are, and you’ve yet to mention any such place. Is it too much to ask that you clarify the matter, and right away?’

And now they fix their eyes harder than ever on Eta. Eta panics.

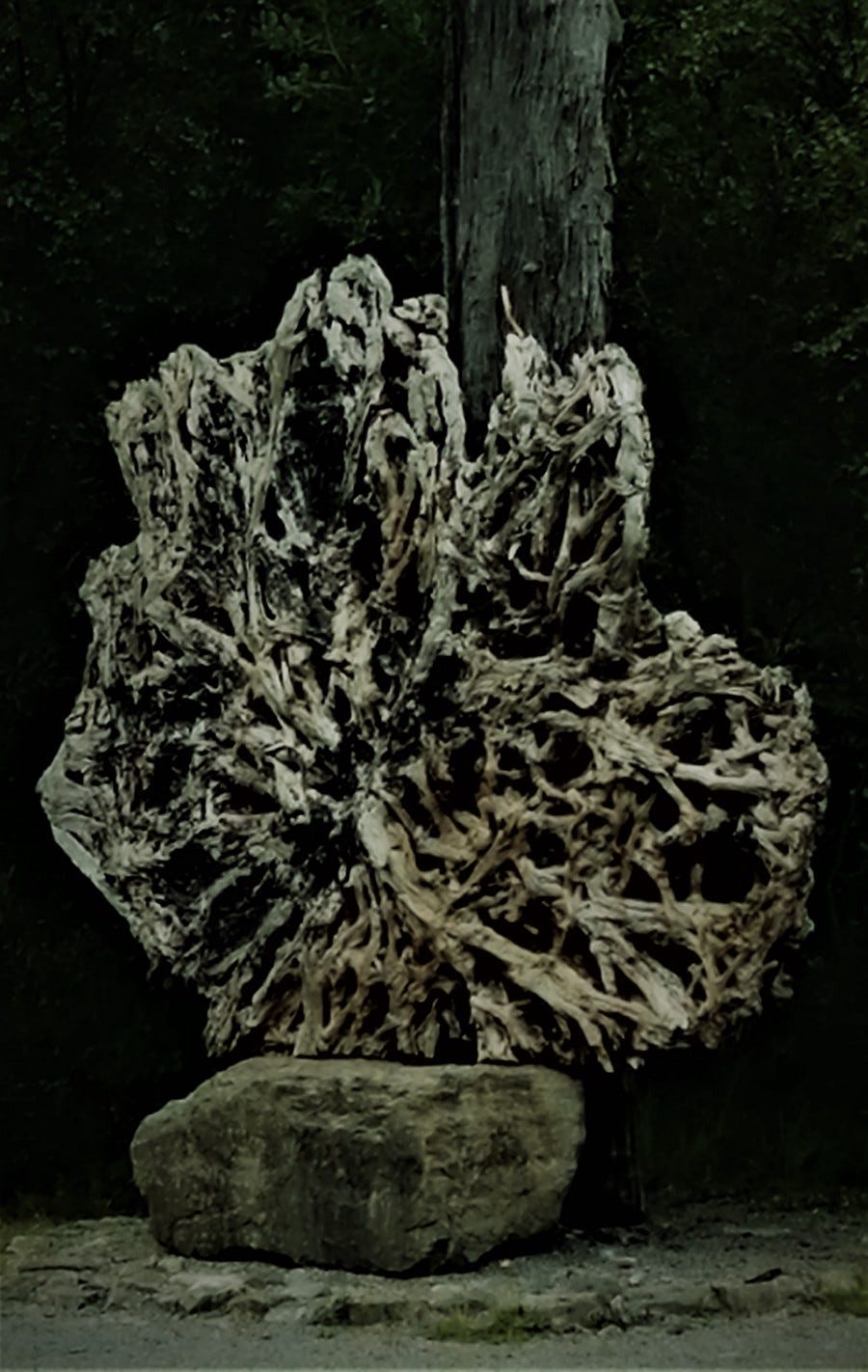

There are all the other Innovations, and then there is the Well. So nicknamed because of its reputation as a “wellspring of creativity”, the overgrown underground mausoleum is the site of the Innovators’ most audacious recent experiments. The last couple of years have seen this ancient chamber spawn a generative pathway so radical that even the Innovators involved can scarcely put words on it. In the innermost sanctum of those holy halls, where the ancestors of the ancestors are said to have assembled not long after the Manifestations gave them life, the boldest inventors of the boldest of tribes are daring to attempt the unthinkable and create life of their own.

True, none of the Constructeds are yet able to stand on their own two feet or think their own thoughts. But the blueprint is there, and no hesitation, tradition or scruple is going to sway the novelty-intoxicated Temels from realising their ambition: the dawn of entirely artificial beings that share all the Forest-dwellers’ strengths and none of their weaknesses.

The possibilities are mind-boggling enough before you consider that creatures that can think just a little more clearly, and work just a little more efficiently, than their own creators will be better positioned to design the next generation of Constructeds than the Temels themselves. Give it a dozen years or so, and the entire course of the Innovations could be in their alien hands. What will they be moved to create, and for what unfathomable purposes? Eta is eager to find out.

The druid doubts Tau and Rho will be quite so enthused. The staunchly devout pair would probably regard the entire enterprise as sacrilegious, even blasphemous: presuming to poach the life-giving power of the Manifestations themselves, and on holy ground the other tribes had always thought remained undiscovered and undiscoverable? What could be more arrogant?

How could I ever make these wearisome traditionalists see that the best way to show your gratitude for the intellectual and creative powers you’ve been given is to make full use of them? Eta has often thought. That an automaton-powered society is one capable of unleashing abundance for all, liberating Forest-dwellers of all tribes from drudgery forever? In such a world Rho would have nothing to do but wander; Tau would have nothing to do but contemplate. And yet Eta is positive both would rather die than help bring it about.

Eta sits frozen in place, a single thought taking up all the available room in their skull: I can’t tell them about the Constructeds, I can’t, I can’t, I just can’t. Suddenly, by what feels like the sheer grace of the Manifestations themselves, the druid’s desperation gives violent birth to a moment of clarity. If violating one taboo wasn’t enough to throw the council off the scent of the Temels’ true secret, the only answer is to violate another. Eta decides to forsake the truth entirely and set out on the high-risk, high-reward road of outright invention.

They spread their limbs in an ancient Temel gesture signifying that the speaker is asking for a fair hearing on a matter of utmost importance. ‘If decorum is to mean nothing in this decadent age and you must have it all out, then so be it. Let me tell you all just how sensitive a topic we’ve embarked upon. Cast your minds back to when we were drawing up our various treaties and contracts after the Days of War. You might remember that I was one of the ones who most vociferously argued for the sanctity of life as a core guiding principle — as I recall, only Tau fought harder to enshrine it in writing.’

Tau attempts to interject, but Eta presses on. ‘Return to the present day, however, and throughout the past few cycles the Temels have been hatching at a rate that is genuinely alarming. Of course, it’s unthinkable to end the lives of the young, who have no say in the matter. But at the last meeting of our tribe, it was decided that in these desperate times, the population simply must be controlled — one way or another. If babies continue being born at the present rate, in the next small-moon-cycle the Temels are going to have to reintroduce the practice of sacrificial self-immolation.’

The others look suitably horrified. Eta presses their advantage.

‘Of course, this will be done on a strictly voluntary basis — at least at first. We’ll have to see how the situation progresses. We’ve marked out the spot for the ritual: the volunteers are to throw themselves into an old dried-out well that has gone unused since ancient times. You know how richly symbolic such sites are in a culture as water-derived as the Temels’. I’ve sanctified the site personally, and now there’s nothing left to do but wait and hope it will never be used. But if the Manifestations have decreed otherwise, I can only pray enough of our number will have the courage to put tribe above self and do the right thing.’

Summoning up every last bit of defiance left in them, the druid glares at each of their co-ambassadors in turn. ‘Again, this is strictly speaking no-one’s business but the Temels’, and I have better things to do than sit here being judged by others who aren’t in our position. You now have far more information than you need, and — if you’re sure you wouldn’t mind — I’d like to hasten along and hear what Chi has to say about conditions in the South.’

Eta sits back, exhausted. They note that Tau and Rho, reeling from upset after upset, seem to have accepted defeat at last and moved their attention over to the brooding Chi. Of course, this small victory has come at the cost of releasing valuable state secrets and telling increasingly outrageous falsehoods, and accordingly there’s nothing manufactured about the druid’s resentful air, or the combatant shivers running through their hydrous frame. Begrudging every second spent protecting secrets they feel shouldn’t have to be secrets in the first place, Eta sits brooding on their west-facing throne, thinking about how best to proceed from here.

On the Temel’s left, Chi is equally deep in thought. Why was Eta so keen on doing these in-depth status reports if they had more than any of us to hide? runs their inner monologue. Were they fishing to see how much the rest of us knew about them? Or are they hoping to gain some strategic advantage by finding out more about us? If so, are they looking for anything in particular?

Eventually the monologue stutters to a halt. Chi has spent most of their life aspiring to the cool-headed ideals of the First Principles, but rationality can only take you so far. A single thought emerges from the blackness. I’m sick of playing games, it says. Let’s throw everything at them and see what happens.

Chi reaches behind their throne, draws out their magnificent stone sceptre, handles it reverentially, taps it twice on the floor. They draw their monochrome torso up to its full height. It’s time.